Protecting the Jefferson River

Story and Photo by Ben Pierce of The Bozeman Daily Chronicle, 06/19/2008

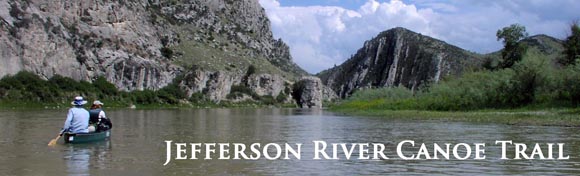

The Jefferson River forms at the confluence of the Ruby, Big Hole and Beaverhead rivers north of Twin Bridges. It flows for nearly 80 miles through rich farmland between the Tobacco Root Mountains and the Boulder Batholith before joining the Madison and Gallatin rivers to form the Missouri River at Three Forks.

For generations the Jefferson has provided a vital water supply for ranchers in the valley, but extreme drought conditions that have persisted since 2000 have taken a toll.

To help deal with the drought local ranchers, community leaders, businesses and landowners have teamed up with Trout Unlimited for the Jefferson River Watershed Project - a cooperative effort to improve the fishery and flows on the river.

Recent work on the Parrot Ditch - an irrigation system that runs 27 miles along the east side of the Jefferson between Silver Star and Mayflower Gulch - could have a significant impact.

"The problem we have on the Jefferson is that it is 80 miles long and only has 12 tributaries," said Bruce Rehwinkel of Trout Unlimited. "At low flow there is only about 60 cubic feet per second (cfs) coming into the whole drainage. So we have to live with what comes in from the top - the Ruby, the Beaverhead and the Big Hole."

And what's come down from the top in recent years hasn't been much.

Since drought conditions beset the region in 2000, summer flows on the Jefferson at Twin Bridges have averaged 900cfs. Multiple times over the past seven summers flows have dipped as low as 280cfs. Between Twin Bridges and Waterloo Bridge just south of Whitehall there are water claims that exceed 800cfs. The normal amount of water diverted into irrigation ditches on those claims is 450cfs.

"If you only have 280cfs coming in and people need 450cfs to run you have some real management challenges," Rehwinkel said.

The Jefferson River was long ago recognized as a chronically-dewatered stream by the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks. In 1988 drought conditions were so bad that flows dropped to 4.7cfs at Waterloo Bridge - the hardest hit area of the Jefferson. Tensions between ranchers, recreationists and landowners reached a boiling point.

"Agricultural uses were defensive and protective of their water and they kind of felt like anyone else that talked about the water was going to take it away from them," said Joe Schlemmer, president of the Parrot Ditch. "There was just this constant battle. When the river got low and the farmers needed their water, it got ugly."

Since 2001, efforts by Trout Unlimited and the local community helped establish the Jefferson River Watershed Council and a voluntary drought management plan that has helped alleviate the effects of drought on the river.

Hard feelings and contentious attitudes concerning water rights have been replaced by a spirit of community and cooperation.

"I think what we have found out in the last few years ... is that we each can have our own interests and support one another," Schlemmer said. "Montana water law is still Montana water law - first in time, first in line. They are still protective of that, but I think the old water rights have become cooperative in saying if we all give a little, we all have a little a little longer."

Two projects on Parrot Ditch are aimed at keeping more water in the Jefferson. The Wiengardt structure just east of Silver Star and the Kurnow over-flow structure east of Willow Springs were completely reconstructed between March 1 and April 17. Both structures are used to regulate flows in Parrot Ditch.

"They were old wooden structures and they leaked and we actually measured how much they leaked," Rehwinkel said. "That's what we based our projections on - 6cfs, three at each of these structures could be saved if you had a gate that could shut off. The old wood gates, the finest control was the height of a two by six. Now you have a screw gate that you can get quarter-inch intervals."

The goal is to improve the ditch in conjunction with other efforts on the Jefferson to maintain a target stream flow of 50cfs at Waterloo Bridge.

Dean Hunt, a rancher on the Parrot Ditch, runs around 300 cows for which he crops around 500 acres worth of alfalfa irrigated by water from the Jefferson River.

"In my industry, the ag industry, you just spread it as far as you can and do the best you can with it," Hunt said. "The thing Bruce has been involved with with TU has been to restore some of our gates that were inefficient and leaked badly. Some of those things can save a little bit and every little bit helps."

In addition to water conservation measures, Trout Unlimited has done extensive work to improve fish populations on the Jefferson River.

Traditionally recognized as a brown trout fishery, the river sees about 5,000 angler days a year, Rehwinkel said. That's down significantly from the more than 20,000 angler days the river saw before the catastrophic summer of '88. Late summer closures and low flows have kept many anglers away.

Long-term fish numbers in the Jefferson average 700-800 per mile; significantly lower than the nearby Madison and Gallatin rivers. Those populations may dip as low as 200 fish per mile during periods of extreme drought, as has been the case the past several years, Rehwinkel said.

Trout Unlimited has done extensive work on a number of spring creeks that feed the Jefferson in hopes of establishing healthy spawning and rearing areas for trout. Rainbow trout numbers have been on the rise and thus far reports have been positive.

"From the fisheries aspect it is pretty straightforward and nobody seems to be questioning it," Rehwinkel said. "I really believe that with this rainbow component that has been added ... that it is not being excessively optimistic to talk about returning the river to 1,200 fish per mile."

It has been an upstream battle for trout and ranchers alike, but progress is being made a spirit of optimism has wept across the valley.

"It has not been without sacrifice," Schlemmer said. "Some of those years we chose not to take all the water we could have with the idea that it wasn't enough to benefit us that much more anyway. And it cost crops. There were fields up and down here that were burning up and not running, so there has been a price to pay for it. But I think on this end of it there has been a benefit because everybody feels like if it is low, we don't have to go fight for what's there.

"And the bottom line is that when you have a healthy river it is better for everybody."

Used with permission of the Bozeman Daily Chronicle.

Jefferson River Chapter Membership: Join us Today!

Jefferson River Chapter Membership: Join us Today!